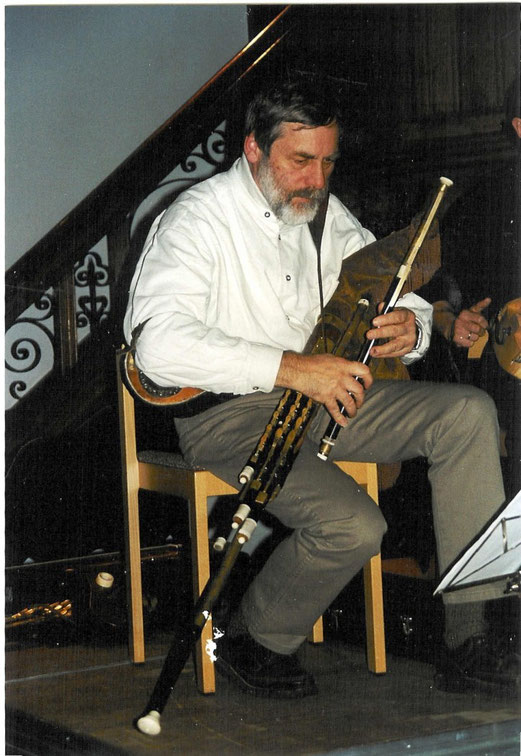

Tom Kannmacher plays Irish Uilleann Pipes – sometimes building parts for them

How I started

The first time I have met with the uilleann pipes was when Finbar Furey played them in a radio program in 1972 which I tumbled in by accident, switching on the radio. They enthralled me immediately, and they kept fascinating me up till the present day, although I tried my hand on many other wonderful instruments. I swapped a concertina against a Dan Dowd practice set in 1976 and started off practicing with the tutor from the Armagh Piper’s Club. In 1977, I knew that I would successfully learn to play the pipes and ordered a full set straight away from John Addison, (who died tragically in1991) which I collected the same year. However, in these days the younger makers in a non – Irish environment were struggling and experimenting a lot, so these pipes had a number of false dimensions and tunings that had to be corrected before playing. So I learnt all aspects of adjusting, reeding, tuning and maintenance, experiences which helped a lot when I later tried my hand at making parts and taking over second – hand sets. Today this very instrument is in perfect condition and tuning (with a Rogge chanter, the original chanter being joined to another Addison set, and self – made bellows.)

I collected more sets to be equipped for any musical demand to be faced as a piper. By now there are at hand:

4 practice sets to be lent to students,

an Addison half set for tuition,

two concert pitch Addison,

a narrow bore concert pitch Podworny & Reusch,

a C set by Robby Hughes,

a set in c sharp, formed out of a Kiernan half set body, home made regulators, bag and bellows and a 19th century chanter.

Besides there are a number of chanters in all pitches between Bb and e.

The Role of A German Irish Piper

The uilleann pipes are the centre of my music. As I am not of Irish descendence, for a long period since I had started playing them in 1976, I had the feeling of not to be taken serious as a piper, both from the Irishman’s point of view, but also from my own.

This sight was changed when I found the early tutors and collections which show that this instrument was not traditional in the sense of today’s understanding when it was invented around 1740. The inventors – not known till the present day – did a great job by joining a baroque oboe to bag and bellows, known from the musette de cour and its descendents, the bellows – blown pipes around the Scottish border, so to have two octaves at hand, easily achievable by overblowing. They called it “New pastoral pipes”, a term which came from the art musician’s sight, in continuance to the French court music of Louis XIV. Still a better achievement was finding ways to play pauses by stopping the chanter on the knee, enabling the player to put modest dynamics into the melody at the same time. Maybe it was the Germans who contributed the common drone stock with its drones side by side (“in union” as opposed to the single stocks of the Great Highland Pipe) in the shape of their “Hümmelchen”, which influenced the shaping of the Northumbrian Pipes. And there were some kind of regulators to be found on the Italian sourdellina. But it seems that it was an Irishman who put all parts together to create this ingenious wonderful bagpipe.

It was an instrument designed for Irish and Scottish airs and composed melodies of similar pattern, to be played in concert or at home by and for the well-to do, who had interest in the revival of Irish and Scottish music, and who could afford such an instrument. (It cost the amount of money you might have payed for a house, then.) And the old sources like the Millar Collection show that the arrangements, embellishments and articulation of tunes followed the patterns of art music rather than those of the the traditional styles which we are accustomed to nowadays pipers.

So I feel much better now, being in good company with the players and listeners of the “first life” of these pipes, using the pipes as an instrument apt for playing all kinds of tunes and melodies which the chanter and accompanying pipes may render convincingly, be it Bach or jazz. But be sure that the Irish traditional material still forms the very core of my repertoire (around 700 pieces by now), which enlarges all the time by the sessions I take part in, by listening to media and by browsing the printed collections.

I like playing concerts, displaying the impressive musical potentials to an audience which, here in Germany, is used to the simply – constructed „Dudelsäcke“ (the word literally means „tootling bags“ ). The core of my repertoire surely is the Irish traditional music proper, the reels, jigs, hornpipes, studied thoroughly by means of all the fine publications of Na PÍobairí Uilleann. The playing of Séamus Ennis, Willie Clancy, Paddy Moloney and Robbie Hannan are only a selection of the stylistic inspirations which are guiding me. My own hallmarks in my piping style is the extensive use of staccato articulation and vibrato, this also inside of dance music, well – understood slow air phrasing on the grounds of being fluent in Irish, and no reluctance to use the regulators, including the self – constructed keys for e’. On three of my full sets I have set-up for changeable drones at hand, to be changed to pitches d, e, g, a b during playing, the “multidrone setup” which I have constructed during the last five years. For details see below.

Having learnt the vocabulary and language of the piping art, I am open-minded enough as to use the pipes in music different from Irish traditional music. So, over the decades, I have put a number of programs on stage in which I try to find new insights into old music styles:

Music by Tourlough O’Carolan,

Playing melodies by J.S. Bach and his contemporaries on the pipes,

Improvisation in the style of Jazz and world music,

Enhancing the lecture of poetry or storytelling with carefully selected traditional airs and tunes

Exploring the earliest collections, published for pipers, to find out about the repertoire and style of playing in the period of its first appearance…

Finding the best posture and dimensions

Playing a number of different sets, and changing between them according to the different musical projects to be faced, I came across the fact that the many dimensions of a given set of pipes is very crucial for the relaxed, supple movements demanded while playing the entire full set with its many simultaneous moving procedures: Moving the bellows, keeping and regulating the bag pressure, fingering the chanter, lifting and lowering it, moving from key to key on the regulators, from the lowest to the top … Each set show different aptness for different movements. So I am studying thoroughly how to guide the students to a posture which is a good basis for developing a technique which would not cause stress, cramp or pain after longer periods of playing.

For myself, besides others, I found a solution which gives me a good chance for holding the chanter as supple as possible: To mount a support onto the chanter top which rests on the left hand upper palm edge, carrying the chanter and taking the task of carrying it while fingering it at the same time. It gives a feeling of security to the playing hands, resulting in much more relaxed finger movements, thus better timing and more precise embellishments.

It is a solution analogous to the shoulder rest which the violin players use, to free the left hand fingers from holding the violin, enabling him to change positions.

I have described these issues in The Piper's Review, Iris na bPíobairí, Vol. XXVI No. 1 Winter 2007: Searching for the proper playing position....

T o m K a n n m a c h e r

T o m K a n n m a c h e r